CDO vs CLO Guide

CDO vs CLO: Understanding the Key Differences

The primary distinction between a Collateralized Debt Obligation (CDO) and a Collateralized Loan Obligation (CLO) lies in their underlying assets. A Collateralized Loan Obligation (CLO) is a portfolio composed almost exclusively of senior secured corporate loans. In contrast, a pre-crisis Collateralized Debt Obligation (CDO) was often a heterogeneous collection of assets, frequently including high-risk mortgage-backed securities.

This fundamental difference in collateral is the principal reason for their divergent performance histories and market perception today.

Defining CDOs and CLOs in Structured Finance

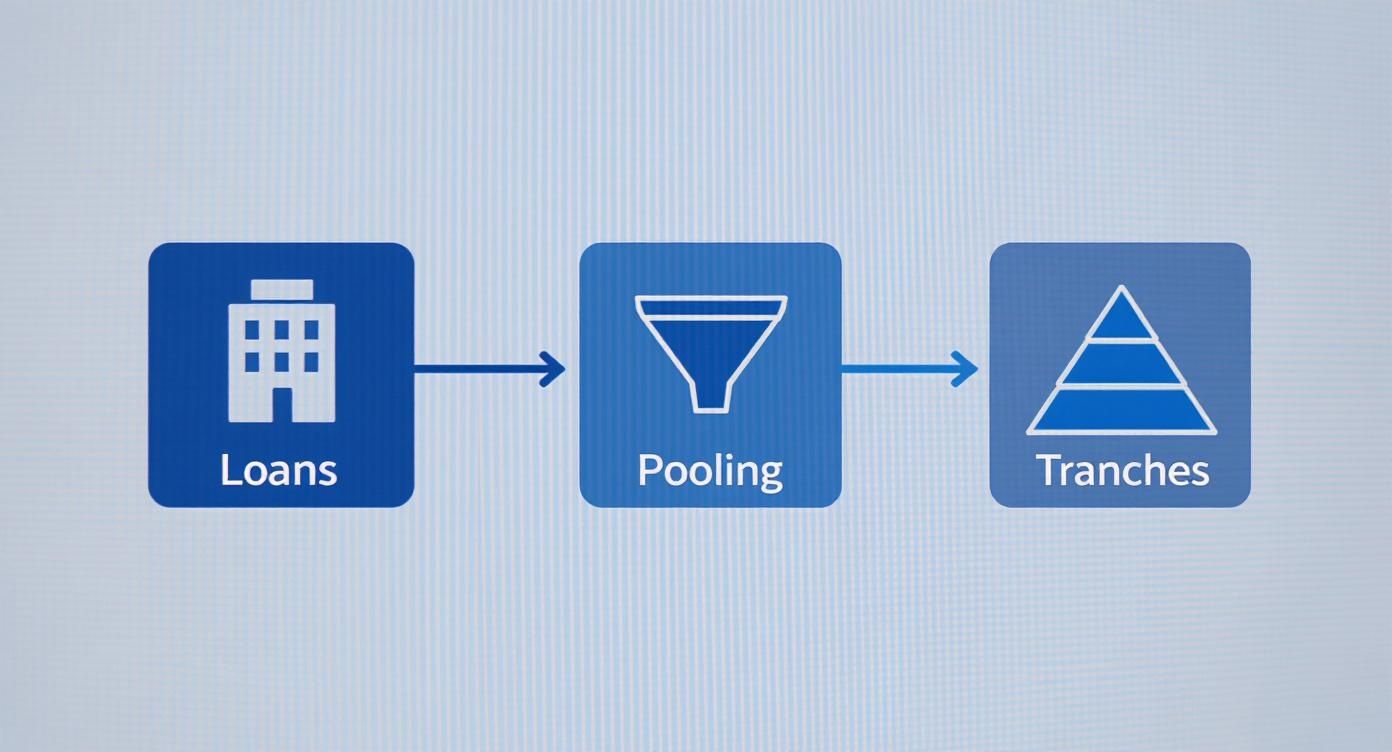

Both CLOs and CDOs are forms of structured finance. They operate on a similar mechanism: pooling cash-flow generating assets, such as loans or bonds, and securitizing them into tranches of debt and equity sold to investors.

Each tranche carries a specific level of risk and potential return, determined by its seniority in the payment waterfall. Senior tranches receive payments first, making them the lowest risk. Junior and equity tranches are paid last, offering higher yields to compensate for their subordinate position and higher risk.

This structure allows investors to select a risk-return profile that aligns with their objectives. However, the composition of the underlying assets is critically different between the two, which is the core of the analysis.

Foundational Attributes

The collateral defines the instrument. CLOs are backed by a specific asset class: senior secured corporate loans, also known as leveraged loans. These are loans extended to established companies and are secured by the company's assets. In a default scenario, holders of these loans have a priority claim on repayment.

In contrast, the archetypal pre-crisis CDO became associated with the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. Many of these instruments were backed by a varied and often opaque mix of debt, including low-quality subprime mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and other asset-backed securities (ABS). The concentration of risk from a single, volatile sector proved to be a critical structural weakness.

The post-crisis period prompted significant changes in structured finance, emphasizing the need for transparency and high-quality collateral. The CLO market persisted and evolved because it was based on more predictable, secured assets compared to the heterogeneous CDOs of the past.

The market has since adapted. Today's CLOs are structured with stronger investor protections and greater transparency, reflecting the lessons from the period that damaged the CDO's reputation. A typical CLO holds between 150 to 250 individual leveraged loans, providing significant diversification within the corporate credit sector. This diversification is evident in transactions like the Voya Euro CLO VIII, where investors can review the portfolio composition and tranche structure. While the market has existed since the 1980s, post-2008 "CLO 2.0" and "CLO 3.0" iterations incorporated major enhancements, including new credit protections and adjustments to comply with regulations like the Volcker Rule.

CDO vs CLO Foundational Differences

This table summarizes the core distinctions between these two structured finance instruments.

| Attribute | Collateralized Loan Obligation (CLO) | Collateralized Debt Obligation (CDO) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Collateral | Senior secured corporate loans (leveraged loans) | Diverse debt assets, including RMBS, ABS, and other CDOs |

| Management Style | Actively managed portfolio | Often static or passively managed |

| Transparency | High (underlying loans are identifiable) | Low (collateral could be opaque and complex) |

| Market Perception | Resilient and structurally sound post-crisis | Largely defunct; associated with the 2008 crisis |

While they share a similar securitization structure, the quality and nature of their collateral are fundamentally different.

Analyzing Collateral Quality and Structure

The discussion of CDO vs. CLO begins and ends with the underlying assets. The quality, transparency, and composition of this collateral determine the risk, performance, and integrity of the structure. It explains why one instrument thrived after the 2008 crisis while the other became closely associated with it.

A Collateralized Loan Obligation (CLO) is constructed on a direct foundation: senior secured corporate loans. These are not complex derivatives but rather loans to established companies for purposes such as acquisitions or operational expansion. The "senior secured" designation is critical—it signifies that in a borrower default, loan holders are first in line for repayment, with claims backed by the company's tangible assets.

This focus on a single, well-understood asset class promotes transparency. An analyst can examine the individual companies in the CLO's portfolio, review their credit ratings, and assess the diversification of holdings across various industries.

The Hodgepodge Nature of CDO Collateral

In contrast, the Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs) from the pre-crisis era were often complex and opaque. While some CDOs held corporate bonds, the instruments that became problematic were frequently collateralized by a heterogeneous, and at times toxic, mix of other debt.

This collection of assets often included:

- Residential Mortgage-Backed Securities (RMBS): Particularly those backed by subprime mortgages issued to borrowers with poor credit histories.

- Other Asset-Backed Securities (ABS): This could include debt backed by auto loans or credit card receivables.

- Re-securitized Tranches: Some of the most complex structures, known as "CDO-squared," held tranches from other CDOs as their collateral, creating layers of leverage and obscuring the underlying sources of risk.

This amalgamation of assets made accurate risk assessment exceedingly difficult. An investor might hold a security backed by thousands of anonymous mortgages and other debts with minimal visibility into their quality.

The critical flaw in many pre-crisis CDOs was not just the presence of risky assets, but the high concentration of assets that were correlated. When the subprime mortgage market collapsed, thousands of ostensibly separate CDOs failed simultaneously because their performance was linked.

How Complexity Amplified Systemic Risk

The complexity of pre-crisis CDO collateral was a significant factor in the 2008 financial crisis. Before the crisis, CDOs were often collateralized with subprime MBS and frequently employed synthetic exposures through credit default swaps (CDS), which increased opacity and risk concentration to critical levels. In 2006, nearly 70% of new CDO collateral was composed of subprime MBS, illustrating the market's concentrated exposure to a single asset class. You can learn more about the post-crisis structural evolution of these securities and their global impact.

CLOs, conversely, have consistently maintained a cleaner collateral structure. Their portfolios consist almost exclusively of corporate loans, intentionally avoiding the re-securitization and synthetic instruments that contributed to the failure of the CDO market. This structural discipline has been fundamental to their resilience and has helped maintain investor confidence. The market learned that transparency and a clear view of underlying assets are essential for long-term stability in structured finance.

Cash Flow Mechanics and Investor Protections

At the core of any CLO or CDO are its cash flow mechanics—the system that collects payments from the underlying assets and distributes them to investors. This process, known as the cash flow waterfall, is the instrument's structural backbone. It determines the priority of payments and, crucially, the allocation of losses. While both structures use this tiered system, the specific construction and built-in protective features differ significantly.

Cash flows from the asset pool are directed down through the tranches. Holders of the highest-rated securities (e.g., AAA and AA notes) receive their interest and principal payments first. This sequential payout is a core feature; it means any losses are absorbed first by the most junior, highest-risk tranches, creating a protective buffer for senior investors.

This infographic provides a simplified visual of the process.

This illustrates how a pool of individual loans is bundled and then tranched into securities with distinct risk and reward profiles to meet different investor requirements.

The Covenants Guarding Modern CLOs

Modern CLOs—particularly the "CLO 2.0" and "3.0" versions developed after the 2008 crisis—are structured with specific protective covenants. These covenants function as early warning systems designed to protect investors by monitoring the health of the loan portfolio. If performance declines, they trigger mechanisms to redirect cash and reinforce the structure before significant impairment occurs.

The two most critical tests are:

- Overcollateralization (OC) Tests: These tests ensure that the value of the collateral exceeds the value of the debt. A senior OC test might require the principal value of the loans to be at least 120% of the outstanding AAA-rated notes. If this ratio is breached, the test is "tripped."

- Interest Coverage (IC) Tests: This test ensures that the interest income from the loans is sufficient to cover the interest payments owed on the debt tranches. It is a ratio of income to expenses.

When a CLO breaches an OC or IC test, the waterfall is altered. Cash that would typically flow to the equity and junior debt holders is diverted to pay down the principal of the most senior debt tranches until the tests are back in compliance. This is a self-deleveraging mechanism that protects senior investors at the expense of those lower in the capital structure.

A Stark Contrast to Pre-Crisis CDOs

Many pre-crisis CDOs, especially those containing mortgage-backed securities, were structured with weak covenants or none at all. Their structures were more rigid and could not adapt when the quality of their underlying collateral deteriorated.

A key failure of many pre-crisis CDOs was their inability to self-correct. Without strong OC and IC tests, cash continued to flow to junior and equity investors even as the underlying mortgage collateral was defaulting, which rapidly eroded the structure's integrity from the bottom up.

This structural weakness meant that by the time senior tranches began to experience losses, the damage was already severe and irreversible. In contrast, the covenants in modern CLOs are designed to be proactive. They initiate a deleveraging of the structure at the first sign of trouble, preserving capital for the senior noteholders. This is a fundamental reason why CLOs have proven more resilient during periods of market stress than their pre-crisis CDO counterparts.

Evaluating Risk Profiles and Performance History

The true test of a financial instrument is its performance during periods of market stress. A comparison of CDOs and CLOs through events like the 2008 Global Financial Crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic reveals two different narratives about risk and resilience, highlighting the fundamental strengths and weaknesses of each structure.

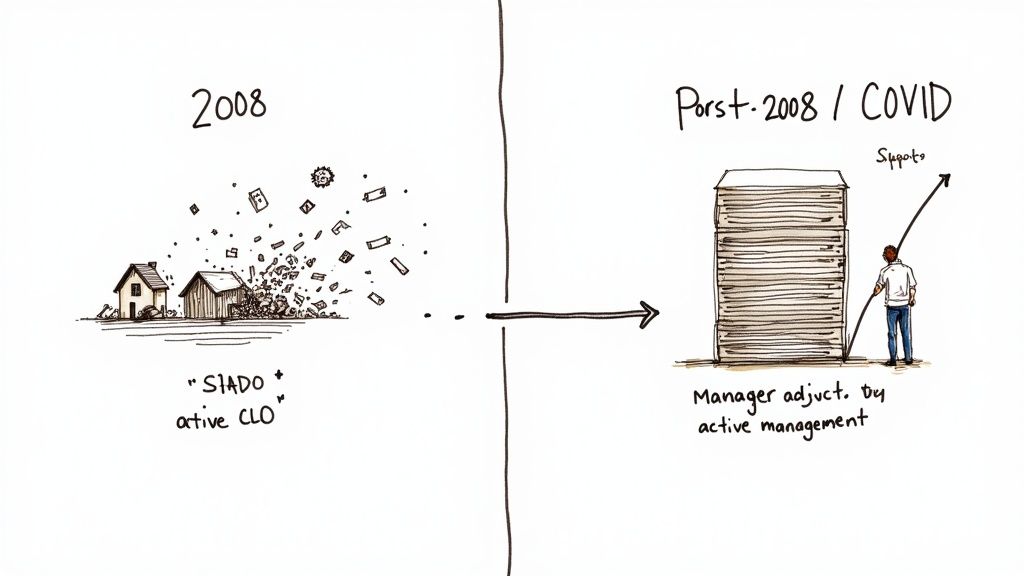

Pre-2008 CDOs were often collateralized with subprime residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS), creating a significant and highly correlated credit risk. When the U.S. housing market declined, these assets defaulted in unison, leading to catastrophic losses and solidifying the CDO's negative reputation. These were static structures, unable to adapt as conditions worsened.

CLOs, by contrast, have a more durable performance record. They are backed by diversified portfolios of senior secured corporate loans, which spreads risk across numerous industries. This diversification provides a structural defense against a single-sector collapse.

Active Management as a Key Differentiator

A critical difference is management style. Pre-crisis CDOs were mostly static pools of assets. Once the collateral was selected, the portfolio was generally fixed. This approach provided no mechanism to sell deteriorating assets or capitalize on market dislocations.

CLOs are the opposite—they are actively managed. A dedicated manager oversees the portfolio and is permitted to trade a portion of the underlying loans within strict guidelines. This provides a toolkit to:

- Mitigate Credit Risk: Sell loans of companies showing signs of financial distress before a default occurs.

- Identify Value: Purchase loans in the secondary market that are trading at a discount but are fundamentally sound.

- Rebalance the Portfolio: Adjust the portfolio's industry exposures in response to changing economic conditions.

This active management is a significant reason for the CLO market's resilience. It is a dynamic defense mechanism that static CDO structures lacked.

Active management fundamentally alters the risk profile. A static CDO represented a passive investment in a fixed pool of assets. A CLO is a dynamic vehicle where professional credit managers can navigate market cycles—a feature that proved invaluable during both the 2008 and COVID-19 crises.

Performance Through Crisis and the "Pull to Par" Effect

Historical performance data supports these observations. CLOs, particularly those issued during distressed periods, have often generated strong equity returns, which is a testament to their structure and active management.

Managers can purchase sound loans when the market is under stress—for example, at 80 cents on the dollar. They hold these loans, collect interest payments, and benefit from the "pull to par" effect. As a loan approaches its maturity date, its price naturally converges toward its full face value. This dynamic helped senior CLO tranches navigate the 2008 crisis with minimal impairment, while many CDO investors incurred complete losses. You can read more about the resilience of CLOs versus CDOs during financial crises to get a detailed analysis.

This "pull to par" is a powerful return driver, particularly for CLO equity investors. When market fear drives loan prices down, it creates an opportunity. As long as the borrower continues to make payments, the discounted loan will eventually mature at 100 cents on the dollar, generating a capital gain for the CLO.

Dissecting the Different Risk Types

Comparing CDO vs. CLO risk is clearer when broken down by category. This clarifies the vulnerabilities and strengths of each structure.

Key Risk Comparison

| Risk Type | Collateralized Loan Obligation (CLO) | Pre-Crisis Collateralized Debt Obligation (CDO) |

|---|---|---|

| Credit Risk | Diversified across numerous corporate borrowers and industries, actively managed. | Highly concentrated in a single asset class (e.g., subprime mortgages), typically static. |

| Market Risk | Primarily driven by credit spreads and default rates in the corporate loan market. | Extreme sensitivity to the housing market and correlated asset price swings. |

| Liquidity Risk | Varies by tranche; senior tranches are generally liquid, while junior/equity tranches are less so. | Became completely illiquid during the crisis as confidence vanished and transparency failed. |

| Structural Risk | Strong, with protective covenants like OC and IC tests that force deleveraging if performance slips. | Weak or nonexistent covenants, allowing value to erode rapidly from the bottom up. |

Ultimately, the divergent histories of CLOs and CDOs are rooted in these core differences in collateral quality, management style, and structural protections. The market learned significant lessons, which led directly to the more robust and transparent structures in place today.

How Regulation and Ratings Forged the Modern CLO

The 2008 Global Financial Crisis was a watershed moment for structured finance. It prompted comprehensive regulatory reform that compelled all market participants, particularly rating agencies, to completely re-evaluate how they measured risk. This new environment established a clear distinction in the cdo vs clo landscape, ultimately reinforcing the CLO's structural integrity and creating a legacy of rigorous oversight that continues to define the market.

Before the crisis, regulatory oversight was light, which allowed for the creation of highly complex and opaque CDOs. The subsequent passage of the Dodd-Frank Act in the U.S. marked a turning point. The legislation introduced critical safeguards, such as risk retention rules, requiring issuers to hold a portion of the securities they created, thereby retaining "skin in the game."

The Post-Crisis Rulebook

These new regulations were designed to align the interests of issuers with those of investors. This was a direct response to the misaligned incentives that amplified the subprime mortgage crisis. Key reforms, such as the Volcker Rule, significantly impacted the market by restricting banks' ability to engage in proprietary trading of instruments like CDOs.

This regulatory overhaul had a profound effect on CLO structures. Modern CLOs are designed to meet these higher standards, requiring far greater transparency into the underlying loans and incorporating robust investor protections. This is a stark departure from the pre-crisis era, where a lack of accountability allowed systemic risk to accumulate. This transparency is evident in modern transactions like the BMARK 2020-IG1 CMBS deal, where documentation and structure are available for investor scrutiny. Similarly, the 2020 CMBS vintage demonstrates how post-crisis structures prioritize transparency and risk mitigation.

The post-crisis regulatory framework bifurcated the market. It rendered the old, high-risk CDO model obsolete while establishing a compliant path forward for CLOs, which were better suited to meet the new demands for transparency and risk retention.

Rating Agencies: A Forced Evolution

The major credit rating agencies—Moody's, S&P, and Fitch—also faced scrutiny for their role in the crisis. Their pre-crisis models failed to adequately assess the correlated risks within CDOs backed by subprime mortgages. They assigned investment-grade ratings to what ultimately proved to be highly toxic assets.

In the aftermath, these agencies were compelled to overhaul their methodologies. The new models are significantly more rigorous and conservative, incorporating several critical upgrades:

- Intensive Stress Testing: Models now simulate severe economic downturns to assess a structure's resilience under extreme pressure, with a specific focus on correlated defaults.

- Loan-Level Analysis: Instead of relying on broad assumptions, agencies now conduct detailed, loan-by-loan analysis of the collateral pools.

- Methodology Transparency: The methodologies and key assumptions behind ratings are now publicly disclosed, allowing investors to understand how a security obtained its rating.

This evolution has made credit ratings for CLOs substantially more reliable. Today's rating process involves a much deeper analysis of a portfolio's quality, a manager's track record, and a deal's structural protections. This analytical rigor provides investors with a more accurate assessment of risk—a lesson learned from the failures of the pre-crisis CDO market.

Key Considerations for Investors

For an investor, the difference between a CDO and a CLO is not merely technical; it is fundamental to risk assessment and capital allocation. While both use securitization, their underlying assets, structural safeguards, and management create two distinct investment vehicles.

Pre-crisis CDOs failed for clear reasons. They contained opaque, concentrated assets and were built with static structures that could not adapt to changing market conditions.

Modern CLOs, in contrast, have demonstrated resilience through multiple market cycles, including the 2008 crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. This is because they hold diversified portfolios of senior secured corporate loans and, crucially, are actively managed by professionals who can trade to mitigate risk. For an investor, this provides exposure to corporate credit with a built-in defense mechanism that older CDOs lacked.

Where Do CLOs Fit in an Investment Strategy?

Determining whether a CLO is suitable for a portfolio involves matching its specific characteristics to investment objectives. CLOs are not a uniform product. The different tranches offer a spectrum of risk and reward, from the relative safety of investment-grade senior notes to the high-yield potential of the equity piece.

The decision depends on an investor's risk tolerance and yield requirements:

- Capital Preservation: The AAA-rated senior CLO tranches are designed for stability. They benefit from significant credit enhancement and have a historical default rate near zero, making them a viable alternative to other high-grade fixed-income securities.

- Yield Enhancement: Mezzanine tranches, typically rated from A to BB, offer higher yields. They carry more credit risk, but for investors comfortable with this exposure, they can be an effective way to generate income.

- Higher Return Potential: The CLO equity tranche offers the highest potential returns. It captures the excess spread—the difference between the interest earned on the loan portfolio and the interest paid to the debt tranches. The potential returns are significant, but so is the risk.

A critical factor for any portfolio manager is that CLOs are dynamic vehicles, not static bonds. A CLO’s performance is heavily dependent on the skill of its manager, making manager selection as important as deal selection.

Analyzing Data with Dealcharts

Proper analysis of these complex structures requires specialized tools. Platforms like Dealcharts provide the transparency needed to examine the contents of a collateral pool, track performance over time, and map the counterparty relationships within a specific deal.

Here is an example of the platform.

This level of detail enables granular, deal-specific research. By using open context graphs, an analyst can trace the data's lineage and build an investment case on a foundation of verifiable information.

Common Questions About CDOs and CLOs

Several questions frequently arise in discussions of structured finance. The following addresses common inquiries about CDOs and CLOs to clarify their differences, history, and current market standing.

Are New CDOs Issued Today?

New CDOs of the type that became prominent before the 2008 financial crisis are generally no longer issued. The combination of high-risk, multi-sector assets is not viable in the current market due to regulatory changes and investor caution.

The market shifted its approach to securitization, moving toward greater specificity and transparency. CLOs have become the dominant vehicle for securitizing corporate credit. While some bespoke structured products may exist, they are typically simpler and operate under much stricter guidelines.

Why Did CLOs Outperform CDOs in the 2008 Crisis?

CLOs performed relatively well during the 2008 crisis for three primary reasons. The most significant was their superior collateral quality. CLOs are backed by senior-secured corporate loans, which provide a priority claim on a company's assets in a default scenario. In contrast, many of the problematic CDOs were collateralized with high-risk subprime mortgages.

Second, CLOs are structured with protective features. Overcollateralization (OC) and interest coverage (IC) tests act as automatic triggers. If the loan pool underperforms, these tests divert cash flow to pay down the senior-most debt, deleveraging the structure. Many crisis-era CDOs lacked these dynamic safety mechanisms.

The third advantage was active management. A CLO manager has the flexibility to trade within the portfolio, selling loans perceived as deteriorating and buying others deemed undervalued. Most CDOs were static, leaving them unable to react as their underlying assets defaulted.

What Is the Main Investment Risk in a Modern CLO?

The primary risk in a modern CLO is the credit risk of the underlying corporate loans. A significant economic downturn would likely lead to an increase in corporate defaults. This would reduce cash flow to the CLO, with losses first affecting the most junior and equity tranches.

Although the portfolio is diversified across industries, systemic economic risk cannot be eliminated. Liquidity risk is another important factor. CLO tranches, particularly the junior and equity pieces, are less liquid than standard corporate bonds. During a period of market stress, selling these positions without a significant price reduction may be difficult.

How Are CLOs Different from Other Asset-Backed Securities?

The key differentiators for CLOs are their collateral of leveraged corporate loans and their active management. This combination sets them apart from most other asset-backed securities (ABS). The majority of other ABS, such as those backed by auto loans or credit card debt, are pools of consumer debt and are almost always passively managed—the initial asset pool remains fixed over the life of the security.

The CLO manager's ability to actively trade loans is a defining characteristic. Managers continuously work to optimize the portfolio by selling credits they no longer favor and buying others they find attractive. This hands-on, dynamic approach is not typical in other major ABS classes, making the CLO a unique instrument in the structured finance market.

Article created using Outrank