A Guide to CMBS

What Is a Commercial Mortgage Backed Security Explained

A Commercial Mortgage-Backed Security (CMBS) is a fixed-income investment product collateralized by mortgage loans on commercial properties.

It functions as a portfolio of mortgage loans made on properties such as office buildings, shopping centers, and hotels. These individual loans are aggregated and transferred to a trust. The trust then issues a series of bonds, with varying risk and return profiles, to investors.

The Purpose of a Commercial Mortgage Backed Security

A CMBS transforms a collection of illiquid, private commercial property loans into tradable, liquid securities. This process, known as securitization, facilitates capital flow in the commercial real estate market by connecting property owners seeking financing with investors seeking fixed-income opportunities.

Lenders can originate a commercial loan, which often has a 10-year term, and sell it into a CMBS pool. This transfers the loan and its associated risk off the lender's balance sheet, freeing up capital for new lending activity. For investors, CMBS provides access to commercial real estate debt with defined risk and return characteristics.

Core Function and Benefits

A primary function of CMBS is to connect borrowers with institutional investors seeking fixed-income assets. This creates efficiency and scale in a market that would otherwise consist of individual transactions between borrowers and lenders.

The securitization process allows a single pool of loans to be structured into multiple classes of bonds, known as tranches. Each tranche has a different priority in the payment sequence, resulting in a distinct risk profile. This structure enables a single CMBS transaction to meet the criteria of various investor types, from conservative pension funds to credit-focused funds.

This structure provides several market benefits:

- Liquidity for Lenders: Banks and other loan originators can convert long-term assets into immediate capital.

- Access to Capital: Property owners gain access to a deeper and more competitive financing pool.

- Investment Diversification: Investors can gain exposure to a diversified portfolio of commercial real estate loans.

- Risk Allocation: Risk is distributed among different investors based on their preferences, from senior bonds with lower risk to junior bonds with higher potential returns.

A Closer Look at CMBS Components

To understand what a commercial mortgage backed security is, it is necessary to know the components and participants that enable its function. Each component has a specific role in the security's structure and performance.

The following is a summary of the essential elements of a CMBS transaction.

Key Components of a CMBS at a Glance

| Component | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Collateral Pool | The collection of individual commercial mortgage loans bundled together to back the security. | A pool of 200 loans secured by office buildings, retail strip malls, and multifamily apartment complexes across various states. |

| Tranches | The different bond classes created from the loan pool, each with a unique payment priority and risk level. | A senior 'AAA' rated tranche that gets paid first and a junior 'B-piece' tranche that is paid last but offers a higher yield. |

| Trustee | A financial institution that holds the loan documents and oversees the servicer on behalf of the bondholders. | A large national bank acting as the independent fiduciary for the CMBS trust. |

| Servicer | The entity responsible for collecting monthly payments from borrowers and managing the day-to-day administration of the loans. | A specialized loan servicing company that handles billing, reporting, and customer service for all loans in the pool. |

Understanding these four elements—the loans, the structure, the oversight, and the day-to-day management—is fundamental to analyzing how these securities function. To see these components in action, explore a recent transaction like BANK 2024-BNK48, where you can examine the actual loan pool, tranche structure, and servicer details that make up a live CMBS deal.

The Structure of a Commercial Mortgage Backed Security

A commercial mortgage backed security is structured to transform individual property loans into a single investment vehicle. The process begins when lenders, such as banks and financial firms, originate mortgages for commercial properties.

These lenders sell the loans to an investment bank, which acts as the issuer. The issuer bundles them into a large, diversified portfolio, often comprising dozens or even hundreds of loans from different geographic regions and property types. This portfolio becomes the collateral for the new security. This diversification is a foundational feature designed to mitigate the risk of any single loan default significantly impacting the entire structure.

This diagram illustrates how the final CMBS product is built upon layers of loans, which are themselves backed by physical properties.

It shows the layered nature of the investment—a single security supported by a pool of loans tied to tangible real estate.

The Role of the REMIC

The loans are legally packaged into a special purpose vehicle (SPV), which is typically a Real Estate Mortgage Investment Conduit (REMIC). The REMIC is a separate legal entity—a trust—that holds the title to all the mortgages in the pool. Its sole function is to acquire the loans and issue the CMBS bonds to investors.

The REMIC structure is a key component. It is a pass-through entity for tax purposes, meaning the trust itself is not taxed. Instead, all principal and interest payments from the property owners flow directly through the REMIC to the bondholders. This tax efficiency is integral to the CMBS market.

Understanding Tranches and the Payment Waterfall

The CMBS is divided into different bond classes, known as tranches. These tranches are ordered in a tiered structure often referred to as a "waterfall." Monthly mortgage payments from the loan pool are collected at the top of this structure.

The cash is then distributed sequentially, filling each tier completely before flowing to the next.

This sequential payment structure is how risk and return are allocated. Investors in the top tranches receive payment first, making them the lowest risk, while those at the bottom assume more risk in exchange for potentially higher returns.

The highest-rated, senior tranches (typically with an ‘AAA’ rating) are at the top of the waterfall. They receive their principal and interest first. Once they are fully paid, cash flows down to the 'AA' and 'A' tranches, and so on, until it reaches the lowest-rated (or unrated) tranches at the bottom. This most junior tranche is often called the "B-piece" or the "first-loss" piece.

How Losses Are Allocated

When a borrower defaults and the property is liquidated for a loss, the waterfall structure works in reverse for loss allocation. Losses are not distributed evenly across all investors. Instead, the B-piece at the bottom absorbs 100% of the initial losses.

If losses are substantial enough to erode the entire B-piece, the next tranche in the sequence begins to incur losses. This process continues up the capital stack. The senior ‘AAA’ tranches are the last to be affected, protected by the subordination of all the junior classes beneath them.

This structural protection is why different tranches from the same transaction can have significantly different credit ratings and attract different types of investors. A pension fund seeking stable, predictable income might purchase a senior tranche. A hedge fund targeting higher yields might purchase a junior tranche, accepting the associated risks. To see real-world examples, one can review various CMBS shelves and their COMM series deals to observe how issuers structure these transactions.

From Issuance to Maturity: The CMBS Lifecycle

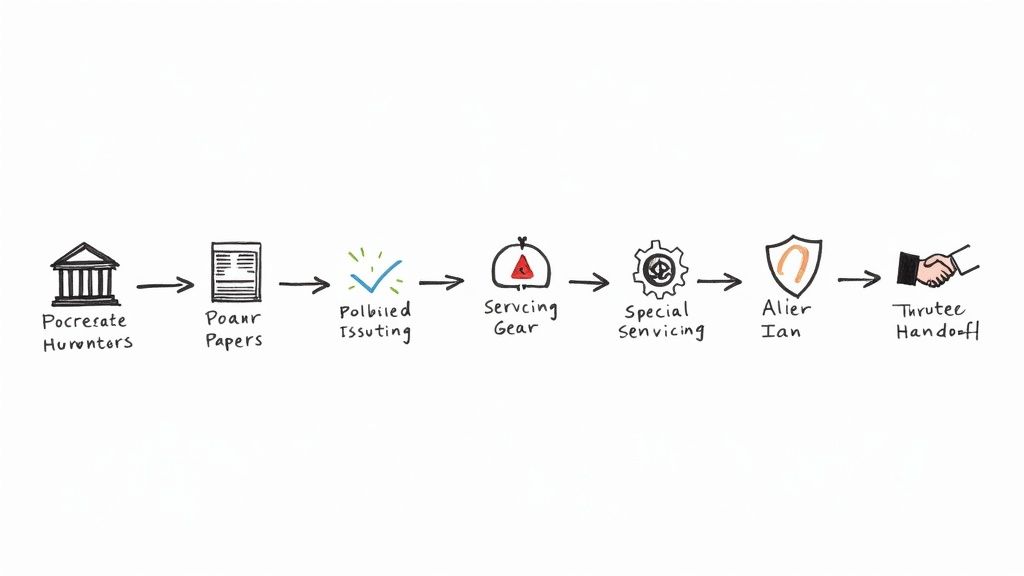

A commercial mortgage-backed security follows an organized lifecycle, managed by specialized entities. This process begins before an investor purchases the security and continues for years until the final loan is resolved.

Understanding this lifecycle is important for grasping how a CMBS is constructed and how it performs over time.

The process starts with origination and pooling. Lenders, such as commercial banks or specialized finance companies, originate individual mortgage loans for property owners. An investment bank, acting as the issuer or sponsor, then purchases a diverse portfolio of these loans. The goal is to create a balanced pool by including different property types, geographic locations, and borrower profiles to distribute risk. The quality of these underlying loans is a primary determinant of the security's future performance.

Key Roles in Managing the Trust

Once the loan pool is assembled, it is placed into a trust—typically a REMIC—and the CMBS is issued to the public markets. At this stage, a new set of participants begins to manage the security for its entire lifespan, often 10 years or more.

Their roles are distinct but interconnected:

- The Trustee: This entity acts as the legal representative for the bondholders. The financial institution holds all loan documents and ensures all other parties adhere to the transaction's governing documents. Its primary function is to protect investors' interests.

- The Master Servicer: This is the day-to-day administrator. It is responsible for collecting monthly principal and interest payments from borrowers, managing escrow accounts for taxes and insurance, and distributing regular performance reports to bondholders. It manages all performing loans.

- The Special Servicer: This is the workout specialist. It becomes involved only when a loan becomes delinquent, such as when a borrower misses payments or defaults. Its objective is to resolve the distressed asset and maximize recovery for the trust, which may involve loan modification, foreclosure, or property sale.

The Servicing and Payoff Phase

For years after issuance, the master servicer maintains operations, channeling payments from borrowers to the trustee, who then distributes the funds down the waterfall to bondholders. This represents the long-term operational phase of the CMBS lifecycle.

Investors monitor the health of the loan pool through detailed monthly servicer reports. To see how this data aggregates, one can review the performance of a specific issuance year, like the CMBS vintage from 2024.

The cycle concludes as the underlying loans reach their maturity dates and are paid off by borrowers. As each loan is repaid, the principal is passed through the trust and distributed to bondholders according to the seniority of the tranches. Once the last loan in the pool is resolved—either through full payoff or liquidation after default—the CMBS is terminated.

The performance of the CMBS market is a reflection of the health of the commercial real estate sector. The demand for these securities is often linked to broader economic trends and lending activity.

For example, market activity can be gauged by the growth in commercial and multifamily mortgage borrowing. This activity saw a 66% year-over-year increase in the second quarter of 2025, with lending for office properties rising by 140% and healthcare properties up by 77%.

Analyzing Risks and Structural Safeguards in CMBS

When evaluating a commercial mortgage-backed security, an investor must assess the inherent risks and the features designed to mitigate them. The value of a CMBS is directly linked to the performance of the underlying commercial real estate loans. Two primary risks are credit risk and prepayment risk.

Credit risk is the risk of loss resulting from a borrower's failure to make required payments. This can occur for various reasons, such as the loss of a key tenant, poor property management, or a downturn in the local economy. When a loan defaults, cash flow is interrupted, and losses can reduce the principal returned to bondholders.

The other primary risk is prepayment risk. This occurs when borrowers repay their loans before the scheduled maturity date, often to refinance at a lower interest rate. While receiving principal back early may seem advantageous, it disrupts the expected stream of interest payments. An early payoff terminates that income stream, and the investor must then reinvest the capital, potentially at less favorable rates.

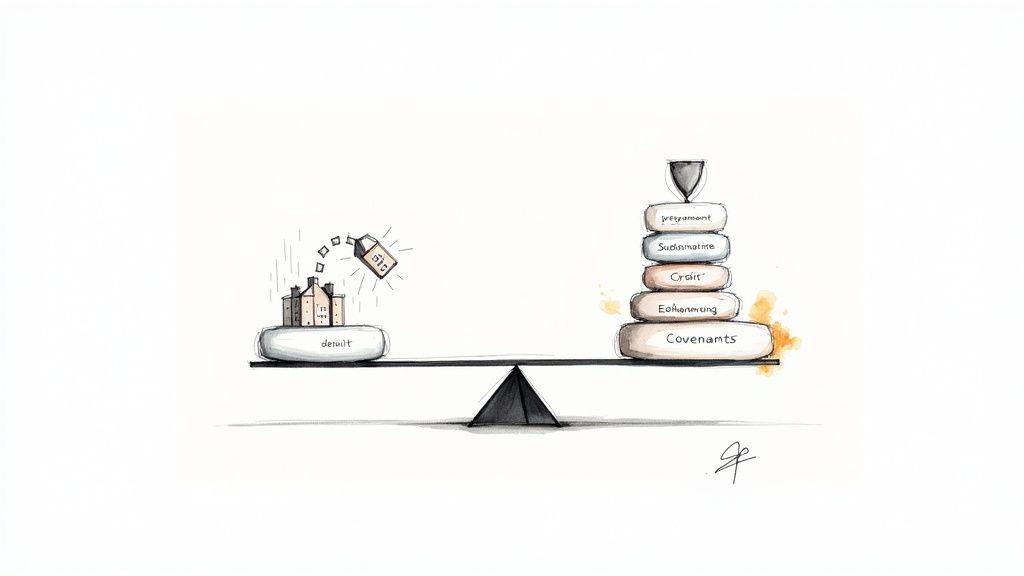

How Structural Protections Mitigate Risk

The structure of a CMBS includes features designed to protect investors, particularly those holding senior, higher-rated bonds. These safeguards are a central reason why the tranched structure appeals to different investor types.

The foundation of this protection is subordination, which is the technical term for the payment waterfall. Any losses from loan defaults are absorbed from the bottom of the capital structure upwards. The most junior tranches serve as a protective layer for the senior tranches, meaning the AAA-rated bonds are the last to be affected by losses. This sequential loss allocation is the primary form of credit enhancement.

A CMBS is a system for distributing risk, where lower-level bonds provide a form of internal credit support for the senior bondholders. The greater the thickness of these subordinate layers, the higher the degree of protection for the bonds at the top of the structure.

CMBS transactions also incorporate specific loan covenants to manage prepayment risk and maintain predictable cash flows. These contractual rules are designed to discourage early payoffs.

- Prepayment Penalties: If a borrower repays a loan within a specified period, a fee is charged. This fee is distributed to the trust to compensate bondholders for lost interest payments.

- Lockout Periods: For the initial years of the loan term, the loan contract may prohibit the borrower from prepaying under any circumstances.

- Defeasance: This process allows a borrower to be released from a mortgage by substituting the property collateral with a portfolio of government securities (e.g., U.S. Treasuries) that generates a cash flow identical to the original loan payments.

The Role of Credit Rating Agencies

Credit rating agencies are independent entities that evaluate the credit risk of CMBS transactions. They analyze the loan pool and the deal's structure, conducting stress tests to estimate the probability of default and the potential severity of losses for each tranche.

Based on this analysis, they assign a credit rating—such as AAA, AA, or B—to each bond class. These ratings provide a standardized measure of credit risk, indicating the perceived safety of each tranche. The agency's rating significantly influences a bond's price and its appeal to different investors. One can see how ratings correspond to specific bonds by reviewing a transaction like the CGCMT 2016-P6 transaction.

Despite these protections, the market faces challenges. In 2025, the CMBS market confronts a maturity volume of over $150.9 billion, with office loans constituting approximately 23% of this total. This pressure coincides with expectations of rising delinquency rates from 4.8% into the higher single digits, which will test these structural safeguards.

How Investors Evaluate CMBS Opportunities

When analyzing a commercial mortgage-backed security, investors employ a disciplined, multi-layered approach. The analysis begins at the security level, evaluating metrics that define its value and performance relative to other fixed-income products. However, a thorough evaluation requires drilling down into the fundamental credit quality of the underlying loan pool, as this is the ultimate driver of returns.

Several key performance indicators at the bond level provide a summary of potential return and duration. These serve as a high-level snapshot for comparing different CMBS deals or tranches.

- Yield: The total anticipated return if the bond is held to maturity, expressed as an annual percentage.

- Spread to Benchmarks: The additional yield a CMBS bond offers over a "risk-free" benchmark like a U.S. Treasury bond. A wider spread typically indicates higher perceived risk.

- Weighted Average Life (WAL): An estimate of the average time each dollar of principal will be outstanding, providing an indication of the investment's duration.

Analyzing the Underlying Loan Collateral

While security-level metrics are a useful starting point, sophisticated analysis proceeds to the collateral. This involves a detailed credit analysis of the individual commercial mortgages within the pool to identify risks and strengths.

Two of the most critical metrics are the Loan-to-Value (LTV) ratio and the Debt Service Coverage Ratio (DSCR).

The Loan-to-Value (LTV) ratio compares the loan amount to the property's appraised value. A lower LTV is generally considered more favorable, as it indicates the borrower has more equity in the property. This equity creates a protective cushion for the lender in the event of default. A loan with a 65% LTV is considered less risky than one with an 85% LTV.

The Debt Service Coverage Ratio (DSCR) measures a property's ability to generate sufficient cash flow to cover its mortgage payments. It is calculated by dividing the property's Net Operating Income (NOI) by its total debt payments. A DSCR of 1.0x indicates that the property generates exactly enough income to cover the mortgage. Investors typically look for a DSCR of 1.25x or higher, which suggests the property can sustain a reduction in revenue without defaulting on its debt service.

By examining the weighted average LTV and DSCR across the entire loan pool, an investor can form a clear assessment of the portfolio's overall credit risk. A pool with a low average LTV and a high average DSCR is considered to be well-structured.

Platforms like Dealcharts enable investors to compare these metrics across hundreds of CMBS transactions, helping identify well-structured deals and assess relative value across the market.

The market for these securities remains active. The first half of 2025 was strong, with issuance reaching nearly $60 billion. This represents a 35% increase over the same period in 2024 and is the highest issuance volume in over 15 years, largely driven by interest rate cuts. More data on these CMBS issuance trends can be found on sites like Trepp.com.

Comparing CMBS to Other Fixed-Income Products

To evaluate a CMBS opportunity, it is useful to compare it against other mortgage-backed securities, particularly Residential Mortgage-Backed Securities (RMBS). Although their names are similar, their collateral and structural differences result in distinct risk and return profiles.

The primary difference lies in the collateral. CMBS pools are backed by a relatively small number of large, heterogeneous commercial loans. RMBS pools, in contrast, contain thousands of small, standardized residential mortgages. This concentration in CMBS means the performance of a few large loans can have a material impact on the entire transaction.

Another key difference is call protection. Most residential mortgage borrowers can prepay their loans at any time without penalty. Commercial mortgages typically include strong prepayment protections, such as lockout periods and yield maintenance penalties. This makes CMBS cash flows more predictable than RMBS cash flows, which is a significant factor for many investors.

This table summarizes the key differences.

CMBS vs RMBS: A Comparative Overview

This breakdown contrasts the core characteristics of CMBS and RMBS.

| Feature | Commercial Mortgage-Backed Security (CMBS) | Residential Mortgage-Backed Security (RMBS) |

|---|---|---|

| Collateral | A few dozen to hundreds of large commercial loans. | Thousands of small, homogenous residential loans. |

| Loan Analysis | Requires detailed analysis of property financials (DSCR, LTV). | Relies on statistical analysis of borrower credit scores. |

| Prepayment Risk | Low, due to strong call protection like lockouts and penalties. | High, as homeowners can refinance at any time. |

| Cash Flow | More predictable due to structural call protections. | Less predictable due to high prepayment variability. |

Understanding these distinctions is fundamental to appreciating why CMBS can offer a different—and often more stable—source of cash flow compared to its residential counterpart.

Common Questions About CMBS

After understanding the basics, several practical questions often arise regarding the rationale behind CMBS and its market participants.

Answering these questions clarifies the purpose of the market, who participates in it, and how it addresses challenges related to commercial real estate debt.

Why Do Lenders Create CMBS Instead of Holding the Loans?

The primary drivers are risk management and liquidity. When a bank originates a large commercial mortgage, it commits a significant amount of capital for an extended period, often 10 years. By pooling these loans and selling them as CMBS, the bank transfers that long-term risk from its balance sheet.

This process offers two main advantages for the lender. First, it frees up capital, enabling the bank to originate more loans and generate additional fee income. Second, it converts an illiquid asset (a commercial mortgage) into immediate cash. For the broader market, this process is essential for maintaining capital flow into commercial real estate.

Who Are the Primary Investors in CMBS?

The investor base for CMBS is diverse but consists almost entirely of institutional investors. These include insurance companies, pension funds, mutual funds, hedge funds, and specialized asset managers.

The tranched structure is what attracts such a broad range of investors. A conservative pension fund can purchase the highest-rated AAA tranches, which offer stable, predictable payments with minimal credit risk.

Conversely, hedge funds and specialized credit investors may purchase the lower-rated "B-piece" tranches. These tranches are the first to absorb losses from loan defaults but offer significantly higher yields to compensate for the increased risk.

What Is the Role of a Special Servicer?

The special servicer functions as a workout specialist for distressed loans. While the master servicer manages the day-to-day administration of all performing loans in the pool, the special servicer becomes involved when a loan encounters significant problems.

A problem loan could be one with missed payments, a major vacancy, or a borrower bankruptcy. The special servicer's sole objective is to resolve the situation in a way that maximizes the recovery of principal and interest for the CMBS trust and its bondholders.

A special servicer has various tools to resolve a distressed loan. It may modify the loan terms, foreclose on the property, or manage the property with the intent to sell it at a later date. The chosen strategy is based on which path is expected to result in the smallest loss for the trust.

Their expertise is particularly critical for investors holding the riskier, subordinate bonds, as these investors are the first to be impacted by any realized losses.

Are All Loans in a CMBS Pool for the Same Property Type?

It depends on the type of transaction. The most common form is the "conduit" CMBS, which is diversified by design. These pools contain a mix of loans secured by different property types (office, retail, multifamily, industrial), located in various geographic regions, and made to unrelated borrowers. This is a deliberate strategy to mitigate concentration risk.

However, Single-Asset, Single-Borrower (SASB) transactions are also a significant part of the market. These securities are backed by a single large loan on a single property—such as a large office tower—or a portfolio of properties owned by the same borrower. SASB deals are not diversified, so their performance is entirely dependent on that single asset or borrower. This represents a distinct risk profile, and distinguishing between a conduit and an SASB deal is a fundamental first step in any analysis.

Article created using Outrank